Datum: 30-06-2015

What immediately comes to mind when I think about cycling in Utrecht is biking through/under the Domtoren. The fact that that such a magnificent structure—about 700 years old and standing more than a hundred meters high—can be cycled through is absolutely remarkable. Where else on Earth can one ride a bike through such an old, ornate building?

Tekst: Pete Jordan

In Amsterdam, of course, stands another grand, monumental building—the Rijksmuseum—with an incredible passageway bike path.

But while the Domtoren passageway was constructed as the grand entryway to a monumental building and then later—after the collapse of part of the Dom building in 1674—was eventually transformed into a thoroughfare, the Rijksmuseum passageway was constructed as a thoroughfare and then, for the past century, Rijksmuseum officials have lobbied (unsuccessfully) to transform it into the grand entryway to a monumental building.

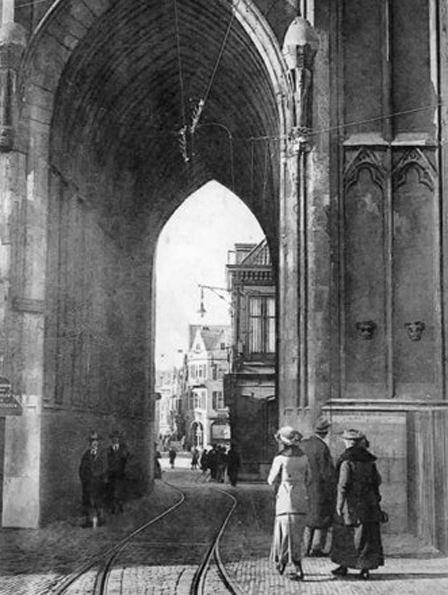

For years the Domtoren passageway was largely the domain of pedestrians. In 1889, the first horse-drawn trams began running through it. This lasted until horse-drawn trams were replaced by electric ones in 1907.

Tram line #2 ran through the passageway until 1938, when the city’s tram network was dismantled and the service replaced with busses. Tram line #2 was succeeded by bus line #2.

During the many decades that the bus ran through the Domtoren passageway, cycling was prohibited. Thus the Domtoren as a bike path is actually a relatively recent phenomenon.

What’s curious about the Domtoren passageway is how many cyclists heading from Servetstraat to Domstraat/Voetiusstraat elect to not cycle straight through the building. Instead they turn and cycle around the building. Of one hundred cyclists biking up Servetstraat towards the Domtoren, 38 of them declined the opportunity to cycle through the grand structure making instead a detour around the building.

The question begs: Why do so many cyclists bypass this magnificent cycling opportunity?

Some theories:

1) Too many pedestrians

Indeed, the foot traffic in the passageway can hinder cycling through it. But the detour route on the Domplein can also be crowded with pedestrians (especially since so much café terrace space now occupies what used to be the roadway). And besides, many cyclists have no such qualms about poking their way through the pedestrians.

2) The legacy of a century of public transportation usage

For so long, cyclists were not allowed to cycle through the passageway because there was simply not enough room to accommodate both the public transportation vehicles and the bikes. The below photo—a still from a 1917 film shot from atop a tram—shows a cyclist coming from Severtstraat avoiding the approaching tram by bypassing the passageway.

As a result of this legacy, it’s possible that a lasting effect is that cyclists who were so used to biking around the Domtoren continue to do so even though the ban has been lifted.

It’s hard to imagine this really having such a lasting effect. Take, for example, the case of the Rijksmuseum passageway. For nine years the Rijksmuseum passageway was closed and cyclists had to follow detours around the building. Since the Rijksmuseum passageway reopened in 2013, it’s hard to imagine (or even see) many or any cyclists opting to go around that building instead of through it.

3) Wind tunnel

The Domtoren is remarkably efficient at catching the wind and funneling it through the passageway. The cyclist pictured below is bent over his handlebars as he pedals into the wind. Do some cyclists avoid this hazard by keeping clear of the passageway?

4) The Utrechtse Studenten Corps urban legend

Once upon a time a UTC member was entering (or exiting) the passageway when a member of a rival student organization leaped from the Domtoren. The rival landed on the USC’er—and survived. The USC’er did not. If the legend is to be believed.

For this reason, USC bans members from using the passageway. And indeed, a large number of those cyclists who detour around the Domtoren appear to be students.

While no record exists of any such incident ever occurring, suicide is routinely committed by people leaping from the Domtoren (four cases in the past six years). But here’s the thing: while detouring around the building may make USC’ers feel safer against falling bodies, actually the route they follow is still within the line of fire of someone leaping from above. In fact, it could be argued, that those taking the detour spend more time in the danger zone than if they had just zipped through the passageway.

In 2012, USC members who ran the Utrecht Marathon received special permission to avoid running through the Domtoren. With the Tour de France route leading passing under the Domtoren, will any of the Dutch riders also seek a special dispensation?

Toen schrijver Pete Jordan(1966) vanuit San Francisco naar Amsterdam verhuisde, liep hij meteen tegen de Nederlandse fietscultuur aan, letterlijk: al bij zijn eerste stappen in de stad reed een van de vele fanatieke fietsers hem omver. Hij raakte gefascineerd door de eindeloze stoet tweewielers in de stad en besloot een diepe duik te nemen in de historie van deze oer-Hollandse gewoonte. Zijn ervaringen als buitenlandse fietser in Nederland verzamelde Jordan in het boek De fietsrepubliek. Van de zwangere vrouwen tot fietsende nonnen, van de handelaren in gestolen fietsen tot de fietsenvissers die fietsen uit de grachten halen. Het resultaat is een unieke blik op een voor ons zo alledaagse bezigheid.